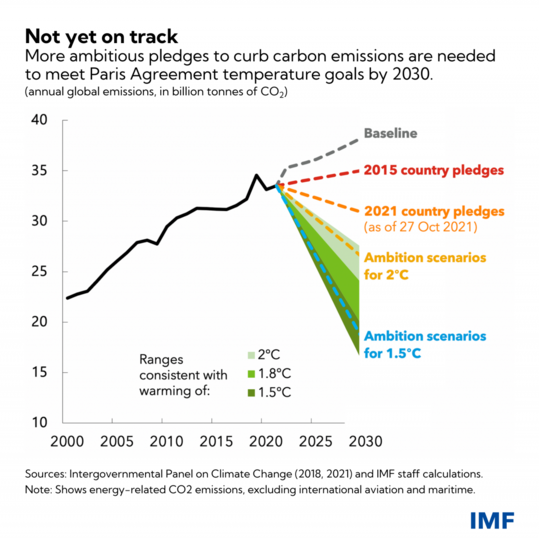

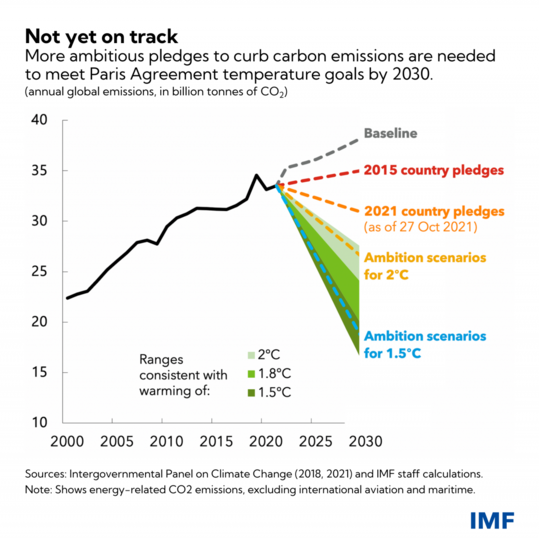

New IMF analysis shows gaps in ambition and policy needed to achieve emissions curbs that contain global warming. In 1785, Robert Burns reflected on how humanity has come to dominate our planet: “I’m truly sorry man’s dominion, has broken nature’s social union,” he wrote. The Scottish poet’s words still ring true two centuries later. Man-made climate change threatens our planet’s ecosystem and the lives and livelihoods of millions of people. From the IMF perspective, climate change presents a grave threat to macroeconomic and financial stability. Now, the window of opportunity for containing global warming to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius is closing rapidly. As world leaders gather in Glasgow for COP26, a new IMF Staff Climate Note shows unchanged global policies will leave 2030 carbon emissions far higher than needed to “keep 1.5 alive.” Cuts of 55 percent below baseline levels in 2030 would be urgently needed to meet that goal, and of 30 percent to meet the 2 degrees Celsius objective. To achieve these cuts, policymakers attending COP26 must address two critical gaps: in ambition and in policy. The global mitigation ambition gap 135 countries representing more than three-quarters of global greenhouse gas emissions have committed to net zero by mid-century. But we fall short in pledges for the near term. Even if current commitments for 2030 were met, this would only amount to between one- and two-thirds of the reductions needed for temperature goals. Advanced economies are expected to cut emissions more rapidly for reasons of equity and historical responsibility. They have collectively pledged to cut their emissions 43 percent below 2030 levels. At the same time, higher-income emerging market economies have together pledged a 12 percent cut, and lower-income emerging market economies, 6 percent. However, the Climate Note shows regardless of how cuts are spread across country groups, everyone has to do more. For example, getting in the range of the 2 degrees target could be achieved with emissions cuts from advanced economies, high-income emerging markets, and low-income emerging markets of 45, 30, and 20 percent, respectively. A different balance of effort with cuts of 55, 25, and 15 percent would achieve the same goal, as would a weighting of 65, 20, and 10 percent. To stay on track for 1.5 degrees, much more ambitious reductions are required for the same groups of countries. For example,70, 55, and 35 percent, or 80, 50, and 30 percent below 2030 baseline levels.  The good news is abatement costs are manageable. To put global emissions within range of a 2 degrees target would cost 0.2 to 1.2 percent of GDP, with the biggest burden falling on richer countries. And in many nations, the cost of shifting away from fossil fuels may be offset by domestic environmental benefits, most notably reductions in deaths from local air pollution. Enhanced external financing will be essential to support stronger mitigation ambition for emerging markets and developing economies. Advanced economies must fulfill their commitment to provide $100 billion per year in finance to low-income countries from 2020 onward. The most recent figures show that we remain short of that target. In addition, to scale up private financing, certainty over public mitigation objectives will be critical, especially price signals to level the playing field for clean technologies. Also critical will be better-quality and standardized information, so investors can help address perceived risks, including in low-income countries. The global mitigation policy gap Even with sufficiently ambitious pledges, we still need policies to implement the emissions cuts. Carbon pricing—charges on the carbon content of fuels or their emissions—should play a central role, especially for large emitters. At a stroke, it provides a price signal to redirect private investment to low carbon technologies and energy efficiency. But the gap between what’s required versus what’s in place is very large. A global carbon price exceeding $75 per ton would be needed by 2030, to keep warming below 2 degrees. At the international level, coordination will be critical to overcome political economy constraints and scale up carbon pricing. Think of concerns about competitiveness and uncertainty over policy actions that make it difficult for countries to act alone. Addressing these issues is at the heart of an IMF staff proposal for an international carbon price floor among a small group of large emitters. Such a floor would be equitable, with differentiated pricing for countries at different levels of economic development, alongside financial and technological assistance for low-income participants. And the price floor arrangement would be pragmatic, allowing for national implementation through non-pricing measures that achieve equivalent outcomes. It would be collaborative, helping avoid contentious border carbon adjustments if some countries move ahead with robust pricing while others do not. At the domestic level, carbon pricing reforms could jump-start emissions reductions. Critically, this need not come at the cost of the economy. Recent empirical studies suggest that carbon pricing reforms have not reduced GDP or employment. Indeed, such reforms could support long-run growth objectives. Revenues from carbon pricing—typically around 1 percent of GDP or more—can be used to reduce labor taxes or increase public investments, helping boost the economy. These are just some examples of how mitigation strategies can—and must—bring wider benefits at all levels of society. Policymakers should ensure a just transition with robust assistance for vulnerable households, workers, and regions. For instance, carbon pricing reforms can be equity-enhancing and pro-poor. If revenues are used to strengthen social safety nets and raise personal income tax thresholds, the policy has net benefits to poorest groups and neutral impacts on the middle class. Alternatively, revenues could be used for public investments in health or education. Another key ingredient of any mitigation strategy is green public investment. We need to accelerate the adoption of clean technology infrastructure like smart grids and charging stations for electric vehicles. Working together, not only do private and public investments in clean energy have especially powerful growth effects, low-carbon industries also tend to be more labor-intensive than fossil fuels which can help boost employment. Lastly, all reforms should also be introduced progressively and well-communicated, so firms and households can adjust. They should also cover broader emissions sources, such as methane, and enhance forest carbon storage. The urgency of action Without an urgent narrowing of ambition, policy, and financing gaps, a dangerous cliff-edge for emissions reductions beyond 2030 will be set up—greatly increasing transition costs, and potentially putting temperature goals permanently beyond reach. An orderly, cooperative, and timely transition can and must happen. Now. In the words of Robert Burns again: “Now’s the day, and now’s the hour.” |

As COP26 gets underway this week in Glasgow, be sure to

As COP26 gets underway this week in Glasgow, be sure to