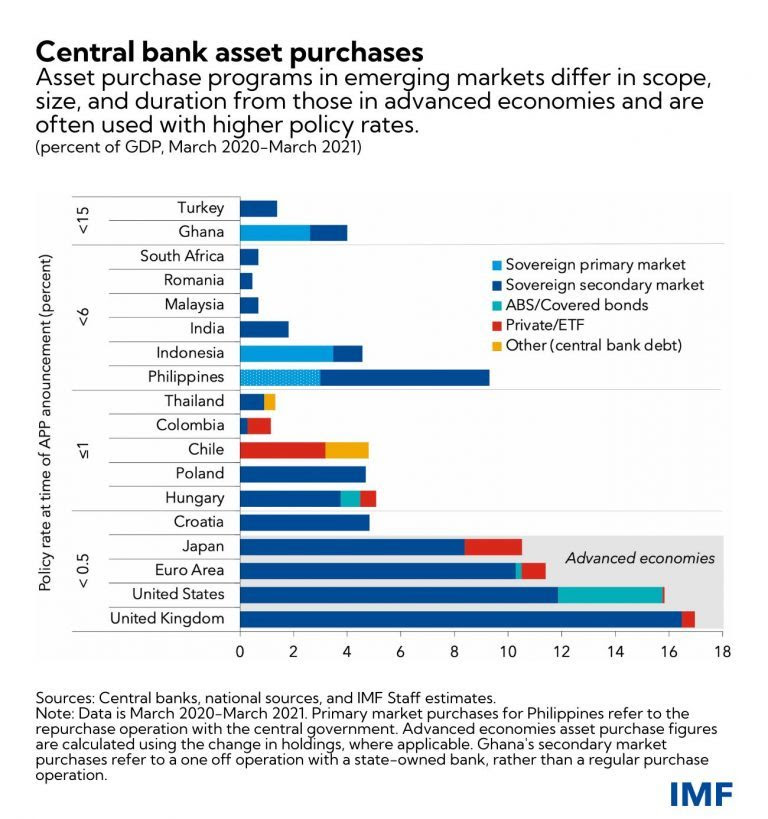

Asset purchases can be an effective tool, but it is critical to minimize risks to central bank independence and price stability. Over the past couple of decades, central banks in emerging markets have made substantial progress in developing the credibility to conduct countercyclical monetary policy. During the COVID crisis, many of these central banks not only cut interest rates sharply, but also deployed a range of tools to help restore market functioning, including asset purchases. And, while some of these central banks now consider moves to tighter monetary policy stances, the likely use of these policy tools again in the future merits a closer look. In previous years, it would have been mainly advanced economy central banks making purchases of government debt. However, for the first time on a significant scale, central banks in countries such as South Africa, Poland, and Thailand broke new ground through their use of asset purchases to combat market dysfunction. While their actions were successful in reducing market stresses, policymakers in these and other emerging market and developing economies need to examine other important considerations as they chart a course forward. Chief among these is whether asset purchases should be viewed as an exceptional response to the COVID crisis, or a more permanent addition their policy toolkits. At the same time, risks ranging from fiscal dominance and debt-monetization to excessive risk-taking need to be navigated. These and other issues are discussed in detail in a recent IMF staff paper. Below, we summarize the findings and provide some preliminary guidance. Asset purchases—useful tools that come with risks Central banks in many emerging market and developing economies have been reluctant to use asset purchases in past crises for fear of engendering a market backlash. As it turned out, targeted asset purchases in these countries during the COVID crisis helped reduce financial market stresses without precipitating noticeable capital outflow or exchange rate pressures.  This overall positive experience suggests that these central banks will also consider asset purchases in future episodes of market turbulence, as discussed in a recent Global Financial Stability Report. However, while asset purchases can help these central banks achieve their mandated objectives, they also pose significant risks. One obvious risk is to the central banks’ own balance sheet: central banks can lose money if they buy sovereign or corporate debt when interest rates are low across maturities, and then policy interest rates rise sharply. A weaker balance sheet may make the central bank less willing or able to deliver on its mandated objectives when policy tightening is needed due to concerns that the required policy actions will hurt its own financial position. A second risk is of “fiscal dominance,” whereby the government puts pressure on the central bank to pursue the government’s goals. Thus, while a central bank may initiate asset purchases—per its mandated objectives—it may find it hard to exit. The government may well grow accustomed to cheap financing from the central bank’s actions and pressure the central bank to continue, even if inflation rises and the price stability objective would call for ending the purchases. The resulting loss of confidence in a central bank’s ability to keep inflation low and stable could precipitate periods of high and volatile inflation. At a recent IMF roundtable discussion on new monetary policy tools for emerging market and developing economies, Lesetja Kganyago (Governor, South African Reserve Bank), Elvira Nabiullina (Governor, Bank of Russia), and Carmen Reinhart (Chief Economist, World Bank Group) underscored the risks posed to central bank balance sheets and of fiscal dominance, but also drew attention to other unwelcome side effects. In particular, while asset purchases could reduce tail risks, such policies could have unintended effects such as encouraging excessive risk-taking and eroding market discipline. And a more active role for the central bank in market-making could inhibit financial market development. Principles for asset purchases Our recent asset purchases and direct financing paper provides some guiding principles aimed at harnessing the benefits of asset purchases while containing the risks. While we see scope for the use of these tools by central banks in emerging market and developing economies—including to help allay severe episodes of financial market distress—a strong and credible policy framework provides an essential foundation. A core principle is that the central bank must have latitude to adjust its policy rate as needed to achieve its mandated objectives. This is critical. Central banks pay for the assets they buy through issuing reserves. These extra reserves could spawn large inflationary pressure unless the central bank can sterilize the reserves by raising its policy rate to a level consistent with price stability. A closely related principle is that any purchases the central bank makes should be on its own initiative, and to achieve its mandated objectives (rather than those of the government). The size and duration of asset purchases should sync with those objectives: purchases undertaken for financial stability should generally be modest in scale and wound down when financial stresses ease, while those to provide macroeconomic stimulus may be larger and more persistent. This principle can best be achieved by ensuring that central bank asset purchases are made in the secondary market, rather than “directly” through primary market purchases or an overdraft facility. Direct financing provides an easy route for the government to determine both the size of the central bank balance sheet and the interest rate that it will pay, tending to undermine fiscal discipline and to increase the risks of debt monetization. Clear communication about both the objectives of asset purchase programs and the rationale for both entry and exit is also crucial. Finally, our paper emphasizes the importance of a strong fiscal position. In particular, the government should be able to provide fiscal backing to cover any losses that may materialize. Such backing is needed to preserve the central bank’s financial autonomy, as well as to allow it to make policy decisions to achieve its mandate—rather than basing the decisions on concern about its (or the government’s) financial position. Moreover, the fiscal authority is more likely to resist the temptation to seek cheap financing from the central bank if its own position is strong. While asset purchase programs may be relatively new territory for central banks in emerging market and developing economies, these principles should help provide a solid foundation. |